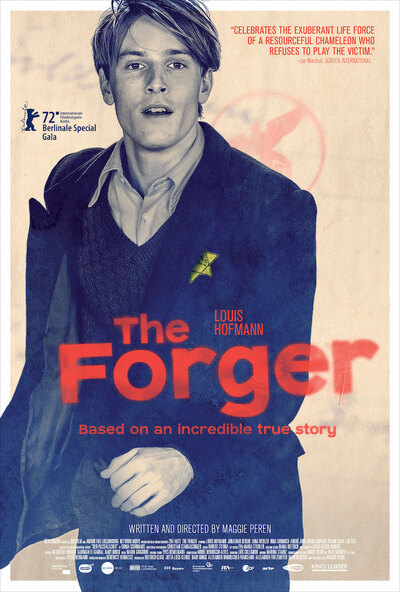

The Forger, by Maggie Peron, based on the memoir by Ciona Schaumhaus.

The Forger was also the name of a movie starring Lauren Bacall and Josh Hutcherson, two actors that I could never imagine had ever starred in a film together. It was one I missed. This one seemed really interesting to me, mainly because of one of the quotes: “celebrates the exuberant life force….” etc.

The only problem I could really see in the movie was, this time, some of the editing and, possibly, the fact that you have to know a little more about Nazi Germany and the Gestapo than what mainstream movies like Schindler’s List have given us.

I really enjoyed the movie, but I think I had to spend… possibly… 30 to 45 minutes trying to figure it out.

Apparently, during the Hitler/Nazi regime, there were quite a large group of Jews in Germany who decided to hide their religion from the Gestapo and practiced being a good German by responding Heil Hitler whenever necessary. But it’s even more complicated than that. And this movie is complicated to a level I haven’t experienced in a long time, which is why it took me so long to understand what was going on – especially what anyone wanted.

So Cioma (I think it’s probably Chris in English but I don’t know) is an exuberant and constantly happy young man. He’s blonde and probably doesn’t have the features that Nazi Germany thought were “Jewish.” But we learn at the very beginning of the movie that his parents and grandmother were “sent East,” and then shortly after, some government official comes to catalogue his mother and father’s room, and the dining room, and then seals it off with an official Nazi tape. He says that all the contents of that room belong to no one. (It’s kind of important that this happens because the theft of Jewish wealth was something that was rampant in the Nazi regime and aided by supposedly “neutral” Switzerland. Believe me: Switzerland was never neutral. They were money launderers and Germany knew it could steal the property and money of the wealthy Jews and hide it in Swiss banks. That’s a crime that is still ongoing in my opinion.

But back to the movie, it took me a long time to understand that being “sent east” was a euphemism for being sent to Auschwitz, or Poland, the eastern front of Germany’s war with Russia (and the rest of the world.) We also have to remember that Poland was invaded by both Russia and Germany. What the Russian’s (Ukrainian’s at the time) did to Polish officers and soldiers is documented in another movie called “Hate.” And it’s worth seeing. But basically, the death camps were mostly located in Poland because it was as far away as they could get. It would be like Americans sending Jews to a desert in Nevada or the hills of Montana. So anyway, I finally started to understand that this guy was Jewish, in 1942, in Berlin. And he even gets called a dirty Jew at one point. It becomes clear he’s not supposed to ride the trolley or take public transportation to his job, where he is making the tubes of rifles (sorry gun owners, I couldn’t name a single part of a gun if I tried, except maybe the trigger). Anyway, I finally come to understand that this job gives him an “exemption,” but even then I thought it meant an exemption from soldiering. I didn’t realize that these words were about the death camps. And yet, he’s relentlessly happy. Even after his parents and grandmother were carted off “east,” he doesn’t seem to give a shit. He has a friend named Det, who seems to work by doing tailoring for “market women.” A lot of this is just impossible to follow without an explanation, which is why it took me so long to realize that there were Jews living in Berlin in 1942.

The plot of the story is that he is an expert artist and can forge documents. True to Germanic culture, the photo of the person had to have grommets on two of the corners, exactly measured x number of millimeters from the the corner of the photos. The photos had to be exact. And most importantly — this is where his talent comes in — the Nazi mark of authenticity had to be exactly 3/4 on the photos and 1/4 on the paper behind it. Also they had a specific font which everyone would recognize today as the “Nazi font.”

He and his friend Det don’t actually have proper documentation of the kind that he is forging for others. What he has is basically a library card, in today’s parlance.

Anyway, I won’t spoil the rest of the movie, but what I wanted to say about it, is that if you don’t know about the world you’re writing about (in my case, the world of underground Jews living in Berlin during the later years of the war, with most of his family already sent to the death camps), the unprepared audience is going to spend most of its intellectual time trying to understand: A) Is this guy Jewish? B) Why do they act like he’s Jewish but don’t do anything about it? C) If he’s not Jewish, why do they treat him so badly? Etc. etc. Do you see what I mean? It’s called world building. The filmmaker’s made a lot of assumptions and possibly Cioma himself when he wrote his memoir. (He made it to Switzerland and ended up fathering four boys.) He understands his experience. I don’t and it took me about 45 minutes until I finally understood what the stakes were. It’s a badly written movie, but I did enjoy it.

And finally… a move. Tonight is my last night in the apartment I’ve lived in for 36 years. I was thinking that I might leave today and spend my first new night at Tom’s mom’s place, but my main goal was to move my plants. Supposedly, some junk people are coming tomorrow to haul my awful furniture away, including my bed and couch, and then the apartment will be absolutely empty except for the few bags of clothing and such that I have left. I’m hoping that I won’t cry when I leave. But 36 years is, I guess, and probably, the longest that I will live anywhere. I can’t say that I’ve really liked it. It was something my dad wanted to do for me. The apartment was always overheated. The building was mismanaged. One time I felt my chair moving and I realized we were having an earthquake and the bizarre north and south design of the building was exacerbating that movement. One time I brought home a guy that was so drunk he wouldn’t or couldn’t be made to leave and I finally dragged him into the hallway – probably one of my worst pick up experiences. People have been extraordinarily nice to me when they find out I’m leaving, and I always want to say, “why weren’t you this nice before.” But Debbie (the broker) said, “But you’re an institution. You’re part of what they see.”

And then I realized, yes, I’m like one of those solid fixtures that you kind of pass by on your way to work and are always happy to see. Mine was the clock on 5th Avenue between 42nd and 43rd or 43rd and 44th. For as long as I worked at Leavy Rosenweig & Hyman, I would look at that clock and judge my pace and situation by it. I took a really nice picture of it on a beautiful summer day. Maybe I’m not entirely human, but I’m humbled by the fact that I’m at least “there,” for people.

Tom Cook