I went to one of the shows that Joel Edgerton appeared afterward for a Q&A, but it was not a Q&A from the audience, but a series of questions from an obnoxious and loud host of some radio station. Actually, I didn’t resent that at all. Indie movie houses need all the help they can get, and his appearance for this talk gave it a sold out house in the middle of the afternoon.

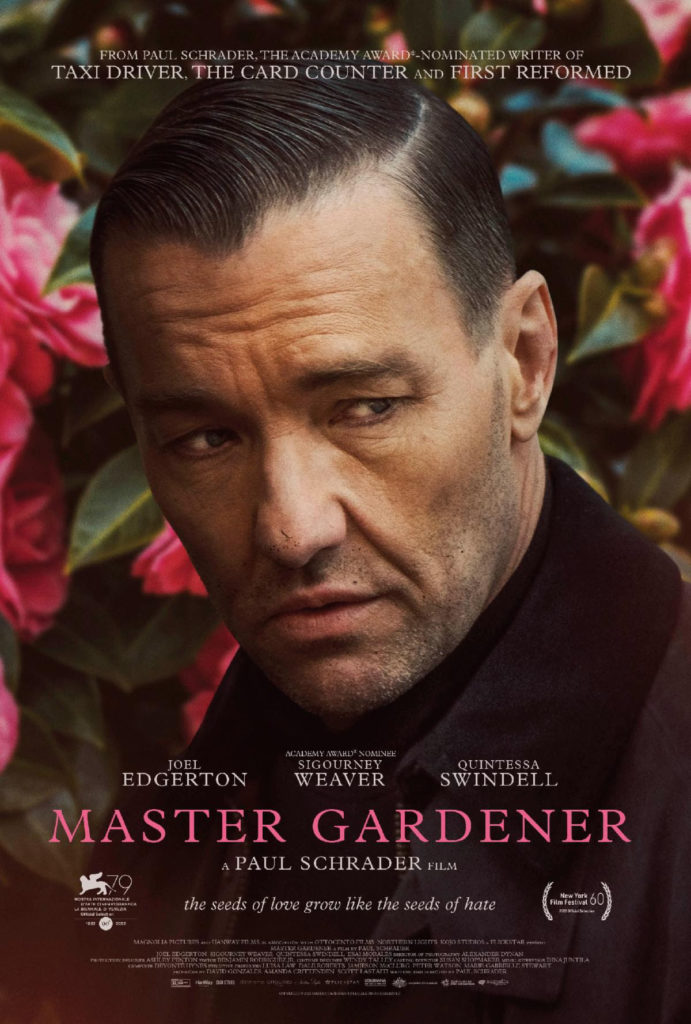

Paul Schrader is one of those writers who has become “important.” So much so that his movies are called “A Paul Schrader” film.

Taxi Driver was my first introduction to his writing and Martin Scorsese, because my film teacher at the time (and I could probably find her name because most of my teachers were famous in one way or another), said, “Well at least we know they (Scorsese and Schrader) have no problem telling us how they feel.”

Through the entirety of this long and boring movie, I kept thinking about Travis Bickel and other Schrader men who are probably what this one is: white supremacists that don’t have a dime and can’t make a buck. Where this anger comes from is a mystery to me. But this is why I felt privileged to hear Joel Edgerton talk. He said, among other things, that his character had to have learned his racism at a young age: it was given to him as a kind of evil gift. He said he was constantly fascinated by the references to racism, but that it was never talked about. And he said that Paul Shrader’s way of directing is to ask his actors not to use their “tricks.” He’s almost Hitchcockian in that way. Hitchcock loathed actors and he loathed what they had been taught to do: show emotion in the Stella Adler school — or basically Stanislavsky. Edgerton said that he had been directed to not reveal emotion on his face, as well as the other actors (Sigourney Weaver and Quintilla someone.)

And therein lies the strangest mystery of this movie: how did this guy, with a white supremacist background, a member of a group like the Proud Boys, (although this group seems a little more serious than the Proud Boys, who seem to like parades more than actual engagement) — how did this guy go from that reprehensible character to a man in love with a young black woman, with a kind of intermediary in the form of the racist character played by Sigourney Weaver.

She is a woman lost in the illusion of plantation life and slave holding life. And apparently, at some point, and FBI agent comes to her and asks her to “hide” in her dilapidated Louisiana plantation as the master gardener. She is still a slave holder, and Schrader uses the scenery to make it clear. He lives in a shack and she lives in a mansion across the road. She has servants. He is a sexual servant. But her house is also devoid of decoration — there’s almost no art or color. There is one maid and I don’t remember the food but it wasn’t lavish. Pointedly, when the Sigourney Weaver character tells him to take her up to her bedroom and make love to her, she says “Take off your clothes,” first, because she wants to stare at his racist tattoos. Later, when he reveals himself to the black girl he’s fallen in love with, she demands that they can continue to be together, but that he must remove them.

Edgerton said that he thinks the reason he kept the tattoos was to remind himself of his past. But he had nothing to say about what caused that change. And that’s where I finally have trouble with the movie and probably many of Schrader’s movies. If we don’t get a chance to understand what’s driving these characters — if they don’t reveal themselves to us with, basically, a way of expressing their innerness — why are we watching them? Yes: action is character. What a person does tells you everything you need to know about their character: what kind of person they are. But sometimes that inwardness can be very rewarding and even surprising, if it’s revealed.

I learned, also, that his named is Edge-r-ton. Not Ed-Ger-ton as I had previously thought.