The preview for this movie makes it seem like this is going to be the biggest tear jerker in a long while, but it’s actually quite bizarre, and that makes it a rather special movie, I think.

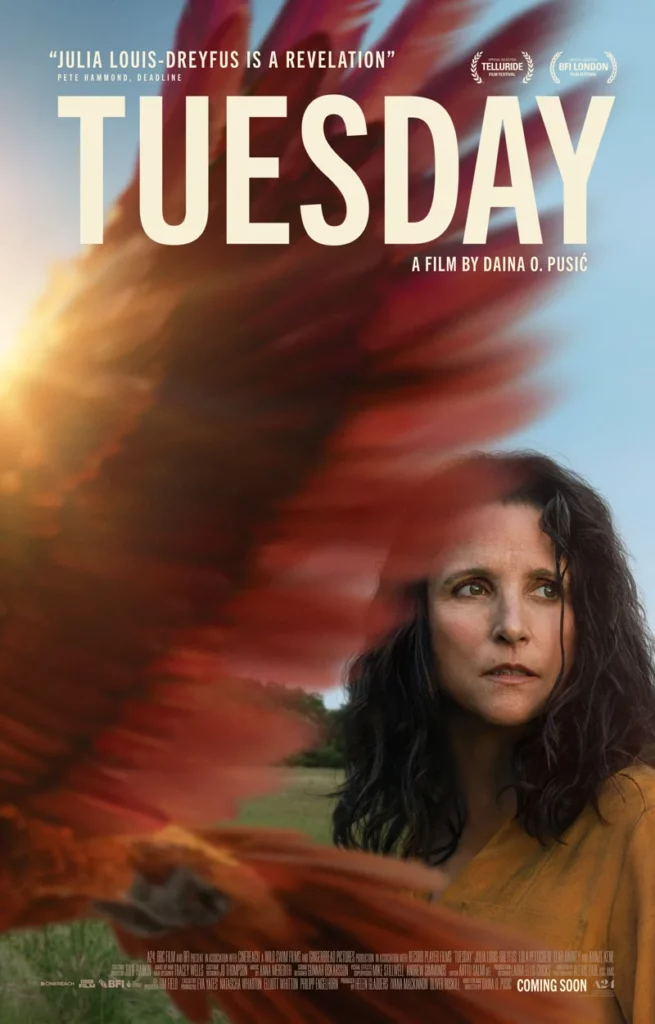

Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays Zora, Lola Pettigrew plays her extremely ill daughter Tuesday, and Arinze Kene plays Death. Death, in this case, is a cockatoo of some kind. (Update: it was a macaw.)

The first scene is of the millions of voices of the earth, reflected in a globe and pulling back through clouds and such in the manner of the opening scene of Contact. But this time, we land not in a human eye but in the cockatoo. He is able to hear all the human suffering going on in the world.

Whenever a voice in pain cries out louder than expected, he makes his way over to that person, waves one of his wings over the person and that person dies. He does this for several different people, and then he hears the cries of Tuesday. He immediately flies over to where she lives in London and when he enters her room, she understands that he is Death and she asks, “Are you here to kill me?” He replies in the affirmative and she asks if he can wait until her mother gets home from work. He reluctantly agrees. He’s covered in soot and dirt so she fills up her sink and lets him take a bath. He turns out toe be extraordinarily beautiful. He can also shrink down to the size of a tear duct or expand, like Alice in Wonderland, to the size of a house. All of this becomes important in several aspects later in the movie.

When her mother gets home from work, she is very obviously avoiding the subject of her dying daughter because she tries to go straight upstairs complaining that things went south at work and they have to start some project over. Tuesday’s home health nurse (this is England where they actually have health care), begs her to stop in and say hello to her daughter. At this point, Death is hiding in Tuesday’s ear canal and her mother doesn’t know it, but at Tuesday’s insistence, death flies out of her ear and grows to a normal size bird. Like everyone in the movie who encounters this bird, Zora knows who or what it is, and on some denial-instinct, beats the bird and smashes it with her foot. Death hobbles out the door and into the garden, knocking over plants and things on the way and just before he can recover himself, Zora starts beating him again with a heavy book. Then she pours alcohol on him and lights a match and burns him until she thinks he is dead. While she’s digging a hole to bury him in, he says, “You need to let her die,” and suddenly with that comment, she grabs the bird — about the size of her hand now — and eats him and swallows him down.

Now, in what screenwriters usually refer to as the vast wilderness of Act II, the most difficult part of a script, the mother and daughter actually get to know each other, and it turns out there are significant secrets the mother has kept from the daughter, which the daughter knew anyway. Zora lost her job a long time ago and has been pretend going in to work and sometimes falling asleep on park benches. To get by, she has been selling all the belongings of the second floor of their house, including many of Tuesday’s favorite things, like dolls. Also, the city starts to become strange and weird. There seems to be an uncontrolled fire at St. Paul’s. There is a man with bloody stumps of legs dragging himself across the road, screaming in agony. Reports come over the radio of cows who were “bolted” in the brain (to become meat), just walking around like zombie cows. Eventually you sort of realize that because Zora “ate” death, nothing can die anymore and the consequences are horrible.

During an argument with her daughter about fixing a light, Zora suddenly grows to the size of the house. And then somehow, either her daughter or herself, she realizes that she has the power of death. So she straps her daughter to her back, grows to the height of the trees and starts walking all over the place, waving her hand to help the suffering people (and cows) die.

But this is a temporary illusion on her part — that she has become death. Because while at a beach with her daughter, she runs off to a secluded place to have a pee and suddenly, for the first time, she hears her daughter’s suffering and pain. This makes her run and eventually puke up the bird. They have an argument and from the daughter’s point of view, she can’t tell what they are fighting about. But whatever’s going on, the bird shrinks down and jumps back into her belly. But he says, “If you don’t tell her, I’ll rip you to shreds from the center of your body.”

And it turns out, all she needed to say was that she didn’t think she was going to survive after her daughter is gone. (That’s in the preview.) This scene did not turn out to be so awful after all, though it was indeed very moving. But what I liked about it is how hard it was for her to get to that simple statement, which seems so very true to all of us. I can’t remember whether the daughter dies at Zora’s wave of the hand or of the birds wave of his wing, but it’s irrelevant. Some time later, it’s clear that Zora is not holding on and is probably suicidal. But then death returns, not to kill her, but to see how she’s doing.

Anyway, it was a delightful movie I thought. I don’t normally look at Rotten Tomatoes for scores or anything like that because usually I think who cares, I’ll never agree. But this one has a hugely divergent rating between the critics and the audience 82 to 49%. I’m firmly with the critics.