It is so interesting when someone who just seems like a throw-away actor — an actor who will probably work but not get many great roles, turns out to be a brilliant writer or director.

But, the thing is, to contradict my calling him a throw-away actor, I did notice Brady Corbet in Melancholia, the Lars Von Trier movie about a very depressed woman’s wedding and her sister’s subsequent nervous breakdown. He had a very small part but it stuck out, sort of like Meryl Streep did in Julia when she only had about 5 seconds of screen time but used it so well it launched her career.

I had no idea what this movie was about. The trailer didn’t give much away but was unusual in that the title moved sideways. And the title is why I went because I’ve always found Brutalism architecture sort of fascinating. Most people are repulsed by it, and it can often resemble those horrible Soviet Union buildings that are cold and intimidating. But Gothic architecture is widely misunderstood too. It’s a matter of seeing, and maybe helping someone else to see.

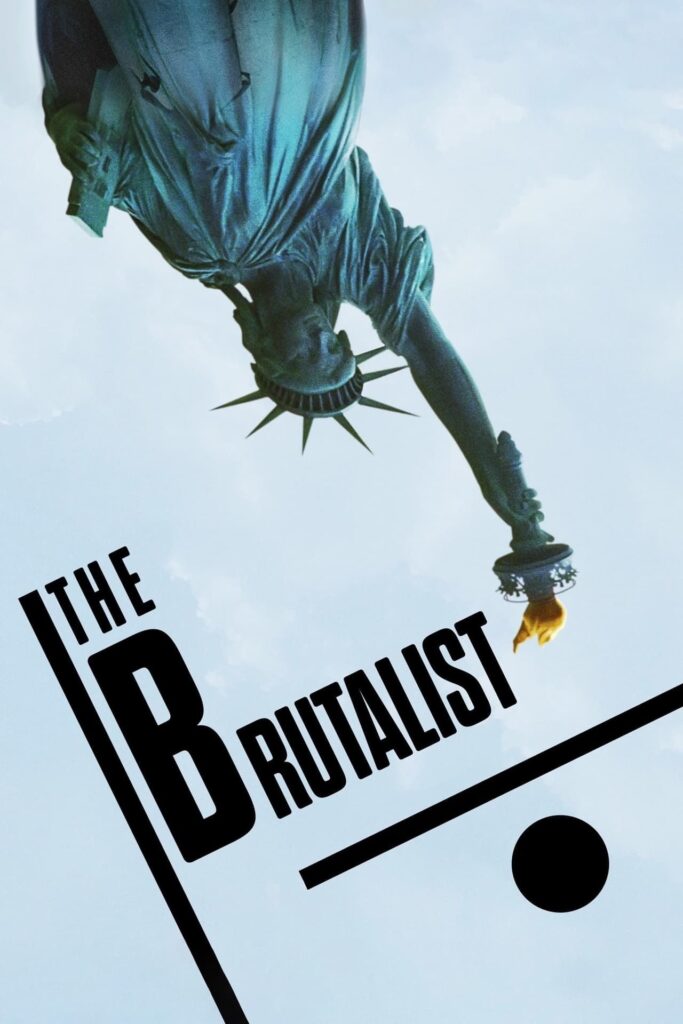

When it began I was so worried that it was going to be one of those handheld nausea movies where the cinematographer or director are trying to capture the feeling of looking around or being distracted, because it began in almost complete darkness with only flashes of light here and there, and a lot of noise and a lot of people, and then suddenly a breaking into the light and the main character Laszlo Toth (Adrien Brody), sees the Statue of Liberty but from upside down, just as the poster shows. Laszlo was formerly an architect before the Nazis separated him from his wife (Felicity Jones) in the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. He studied under the Bauhaus. We learn from a letter that his wife has been able to take their niece, who has stopped speaking, to Russia — until then he didn’t know if she had survived.

He makes his way to Philadelphia to stay with a cousin who has Americanized himself: changed his name to Miller, destroyed his accent as thoroughly as he could, and married a Shiksa. He also converted to Catholicism. He sells furniture, but it’s of the old world style and Laszlo calls it ugly. Although it doesn’t get mentioned explicitly, his wife says she knows a man who can fix Laszlo’s nose and he says something about how he broke it in an accident. None of that’s true. She’s simply trying to make him hide his Jewishness. Eventually accuses him of making a pass and she has him kicked out.

In the meantime he has met an extremely wealthy industrialist Van Buren, whose children asked Laszlo to redesign their father’s library. He did, but in his modern way, and initially Harrison Lee Van Buren, Jr. (Guy Pierce) throws him out in a rage. Laszlo has to go shovel coal on a construction site and live in what looks like a homeless shelter run by nuns. When Van Buren’s new library gets a spread in Look Magazine, he tracks him down, brings him to his mansion, helps him get his wife and niece out of Russia, and commissions him to build a cultural center on the top of this pretty magnificent hill on his property.

There are highs and lows and plenty of arguments because what he is building is a massive Brutalist piece of architecture that no one really understands. It’s all concrete. There are no windows (except there are, but just not where you’d expect). And then a catastrophe which forces Laszlo and his wife to find a new way of living in New York City.

That isn’t the ending of course and the movie is long enough that it actually has an intermission, something I had thought I’d never see again since Titanic. There was something really great about an intermission — everybody running to the bathroom or getting more popcorn and food, quietly chatting, while on the screen there is a clock counting down the 15 minutes. Broadway theatre (not musicals) have mostly given up on the intermission, preferring to cut plays like “Our Town” down to 90 minutes or less. I’ll have to think on it some more because I found the feeling of waiting for the second half really interesting.

So on the way home I was in a cab and I thought, “let me look him up and see whatever became of that building.” Many Brutalist buildings have been torn down.

This is one in Orange County, New York which was partially torn down and replaced with this:

basically so that people don’t have to see it.

Anyway, I couldn’t understand why there was no entry for “The Van Buren Cultural Center,” so I finally just looked up the movie and there were no links to any bio for Laszlo Toth. And then as I read, I realized that I wasn’t watching a bio pic like Elvis or Elton John, where the details are fudged but the gist of his life proceeds basically from start to finish. This was an entire work of fiction. But it so well done I actually left there believing that Laszlo Toth was one of the great architects of the Brutalist movement. The last time something like that happened was with “Possession,” by A.S. Byatt, whose depiction of Randolph Henry Ash and Christabelle LaMotte was so full and humanistic, I had to look them up to see if they were actual historical poets. They weren’t. Like this they were entirely the invention of the writer. That’s when I realized that Brady Corbet, Mona Fastvold, Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones and Guy Pearce made an absolutely monumental work, as they are saying all over the place. This is well worth seeing in the theatre and in 70mm if they have it. It doesn’t open until January but it’s open in Manhattan, probably to qualify for the Oscars.